Changing mindset cures patient and yields New England Journal of Medicine publication

A solved mystery is a thing of beauty. And once solved, it can become a powerful teaching tool. So when an infectious disease team in the Department of Medicine encountered a patient who turned out to have a disease that is common globally but rarely seen in the United States, they engaged in a time-honored tradition in clinical diagnostics: telling a tale.

The format of clinical problem-solving articles in medical journals is an example of teaching through storytelling. In this genre, authors prepare a mini-case summary (including the final diagnosis) for the journal’s editorial staff, along with anticipated teaching points. The UW-Madison authors of the case in question were (pictured at right, in order listed from top to bottom)Joseph McBride, MD, clinical instructor; Alexander Lepak, MD, assistant professor (CHS); and Nasia Safdar, MD, PhD, associate professor and vice chair for research, all of Infectious Disease. Joining them was Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH (not pictured), professor, University of Michigan and Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Center of Excellence.

Once approved for submission — in this scenario, by the New England Journal of Medicine — the next step is to invite a clinical discussant: a clinician who does not know the case in advance and who is not necessarily a subject matter expert in the disease state of the final diagnosis, but who can discuss a broad range of medical topics. The discussant for the case was Gurpreet Dhaliwal, MD (not pictured), professor, University of California San Francisco.

Then, the fun began. UW-Madison authors presented the case in stepwise fashion to Dr. Dhaliwal. Each step, referred to as an “aliquot” (similar to the chemical definition of aliquot as “portion of a larger whole, especially a sample taken for analysis or other treatment”), provided clinical information relevant to the case. “The order in which we released the information mirrored the way in which the case actually unfolded,” said Dr. McBride, who wrote each aliquot in consultation with other authors. Of course, they didn’t lead with the final diagnosis; that would not have mirrored how the case unfolded. In reality, the case involved a 62-year-old woman who sought care at a urology clinic after 15 months and previous visits to 5 health care providers for a relatively common set of complaints: dysuria (painful or difficult urination), hematuria (bloody urine), and polyuria (abnormally large volume of dilute urine).

Framing the Case

The authors had thought carefully about the educational value of the case, and the title they chose for the article gave a nod to their intent. “‘Framing’ is a long-standing art of medicine taught to learners and used on a daily basis by clinicians,” explained Dr. Lepak. “It is essentially how one synthesizes the relevant factors of a case to come up with an impression of what is actually going on. However, framing needs to be dynamic and an iterative process.”

Walking through the case with the discussant allowed a re-enactment of clinical deliberation. “The idea of the clinical problem-solving format is that a clinician is going through the thought process that any other clinician would go through. If we talked about this patient upfront from the beginning in light of all we eventually came to realize, we would describe it in a way that would be a slam dunk,” said Dr. McBride.

So the facts were presented in the initial aliquot summarized what was known at the time: the patient was long-suffering from urinary issues, and had taken several rounds of antimicrobial drugs that had not resolved the problems. Further, cultures were negative, suggesting that bacterial infection was not the actual cause. “….Five consecutive negative urine cultures and ongoing symptoms despite the use of antibiotics make bacterial cystitis a highly unlikely diagnosis," wrote Dr. Dhaliwal. As was the situation in the actual history of the case, he began to contemplate other diagnoses – chiefly, cancer.

“This is exactly what happened,” said Dr. McBride. “Upon imaging, we saw dramatic findings. We thought that perhaps we figured this out: that her symptoms were because of cancer. Only after she got really sick after a procedure did that frame of mind change.”

The Mystery Deepens

Although urine tests had shown no clear evidence of cancer, a computed tomographic (CT) urogram showed a mass on the right kidney as well as further burden of disease on the ureter, stomach, and lymph nodes. "The invasiveness and distribution arouse concern for cancer, although chronic infection is also possible," wrote Dr. Dhilaiwal.

Using cystoureteroscopy to enable more detailed inspection of the bladder and ureter made sense. Unexpectedly, 12 hours after the procedure, the patient presented to the emergency department with fever, rigors, and abdominal pain. Liver function tests indicated hepatitis. There was no resolution of the structural issues noted in the renal system. And the patient was getting increasingly sick: pancytopenia (deficiency in red cells, white cells, and platelets) now accompanied fever and liver inflammation.

After considering both conventional causes of urinary problems and cancer, it was time for a new frame of mind. The clinical team took a detailed history.

This, in the end, made all the difference.

Re-Framing Yields Valuable Information

“Additional history taking revealed that the patient had immigrated to the United States from Guadalajara, Mexico, 18 years earlier,” wrote the authors. She also was raised and worked on a family dairy farm and had frequently consumed unpasteurized milk. Further, she had had a positive tuberculin skin test in Mexico - but one of her friends had experienced a bad reaction to tuberculosis (TB) medication, so she never took the TB medications that had been prescribed.

Both the original clinical team and the discussant came to the same conclusion: it could be a case of genitourinary TB, or possibly Mycobacterium bovis infection that was caused by consuming unpasteurized dairy products.

The practice of medicine is humbling. "If you ask medical students about sterile pyuria, one of the things they'd rattle off is genitourinary TB, but we see it so rarely in the US that recognizing it in real life can be much more complicated than hearing about it in a textbook," said Dr. McBride.

Ultimately, a urine polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for M. tuberculosis was positive, and diagnosis of genitourinary TB was confirmed. Finding a tolerable regime of antimicrobial therapy took some trial and error, but after nine months of treatment, "the patient had complete resolution of her urinary symptoms, pyuria, and imaging abnormalities," wrote the authors.

They had solved the case. So did Dr. Dhaliwal, who concluded that "...the high prevalence of M. tuberculosis in Mexico makes tuberculosis the most likely diagnosis."

Real-World Lessons in Clinical Skills

Arriving at the final diagnosis was not a foregone conclusion; in clinical problem-solving articles, discussants do not always arrive at the correct result. This is not a failing. It’s a fact of the practice of medicine, which is often messier in real life than it is in textbooks. Illustrating that fact was the objective of the co-authors.

For Dr. Lepak, the shifts in thinking provide a real-world perspective. “It was completely rational for the initial ‘framing’ of this case as recurrent urinary tract infection (UTI) or possible cancer due to the hematuria. However, when patients see multiple previous providers, there can be a clinical inertia to the framing process whereby providers (and subsequent providers based on previous evaluations by other providers) get stuck — or ‘anchored’— in a diagnostic rut.”

Becoming unstuck is a fundamental clinical skill, he asserts. “I would love to say that I used some sort of special knowledge to solve the puzzle of what was going on, but it wasn’t special infectious disease knowledge, it was a clinical skill we all can learn to do better. I also can’t take full credit for this skill, as I have learned it from excellent clinical mentors who taught me to think this way, such as Drs. Vogelman, Maki, Andes and Craig. What we want people to take away from this publication is that when things are not adding up or your initial clinical impression is not panning out, the best step is to pause, go back through all the elements of case, and attempt to re-frame the case from a new perspective.”

That perspective can require keen awareness of diseases that are seldom encountered first-hand by a clinician. For example, witnessing a case of genitourinary TB in the United States is a numbers game: Of the 3 billion people worldwide who are infected with TB, only 10 percent develop active disease. In the United States, an annual 10,000 cases of active TB are diagnosed each year. One in 5 manifest outside of the pulmonary system. One-third of these comprise genitourinary TB, resulting in approximately 666 US cases per year, only half of which present with urinary tract symptoms.

A total of 333 patients with genituroinary TB evoking urinary symptoms among a population of more than 325 M people gives pause. “Even for a ‘textbook’ theoretical possibility, we wanted to show that there is a difference between how easily a diagnosis may be made on paper, and in real life, how much more difficult it can be to recognize,” said Dr. McBride.

Arriving at the correct diagnosis required humility, nimble thinking, comprehensive reframing of the entire course of the illness, and an appreciation of the epidemiologic information that was gained with an in-depth history.

More than that, it required the right frame of mind.

Resources:

- McBride JA, Lepak AJ, Dhaliwal G, Saint S, Safdar N. 2018. The Wrong Frame of Mind. N Engl J Med. 378(18):1716-1721.

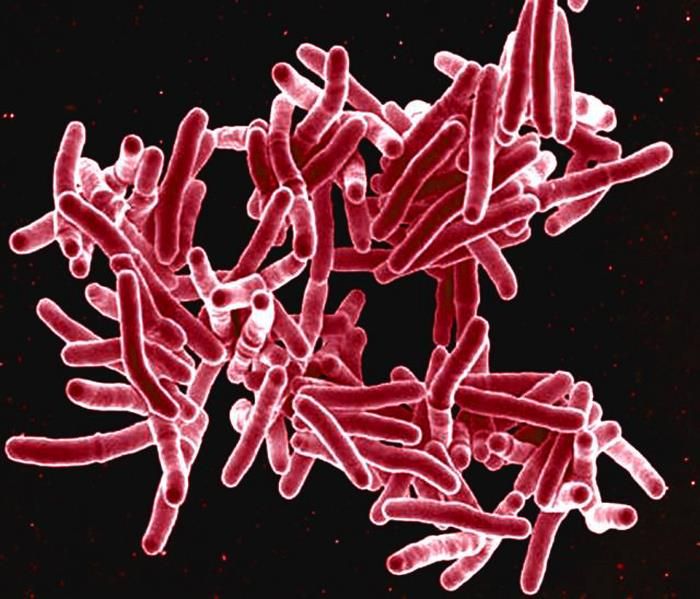

Photo caption (top):Produced by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), this digitally colorized scanning electron microscopic (SEM) image depicts a grouping of red colored, rod shaped, Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria, which cause tuberculosis (TB) in human beings. Image credit: NIH-NIAID